Bioawareness: Going Green With Plant Biodiversity Awareness

Going for a walk in a forest, how many plants and trees can you identify? However, if you saw a koala would you have any problems identifying it? This is the problem that David Jinks, a noted botanist on the Gold Coast discussed in a talk last week entitled Gold Coast Biodiversity.

Charismatic Species

Plants are crucial for creating living ecosystems, yet as this botanist mentioned in his talk, we have “biodiversity blindness”. Unlike animals, plants have a hard time being noticed.

Animals move and are therefore more noticeable. Plants also move but it is quite imperceptible. They grow towards the light, and their leaves move slowly tracking the sun through the day. The leaves of many plants then ‘droop’ at night as it takes energy to keep their leaves tracking sunlight in the day.

We also have a tendency to anthropomorphise animals. Many dress their dogs for instance in clothes. Their furry friends are carefully coiffured to look ‘fabulous’ darlings.

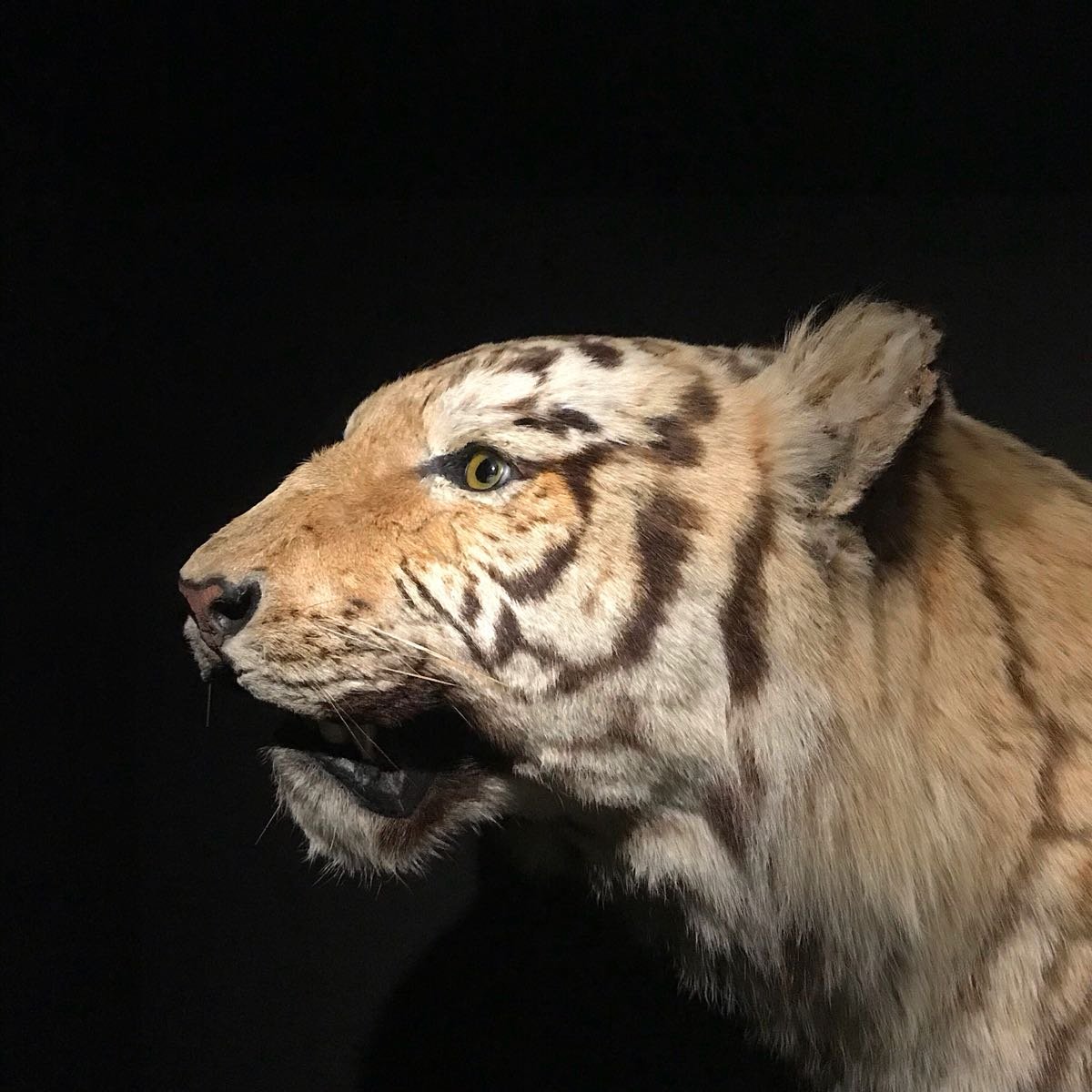

Animals capture our imaginations in a way that plants don’t. Seeing a majestic tiger and hearing it roar reminds us of the power and beauty of nature.

Biodiversity Awareness

Even for someone like myself, who I consider ‘bioaware’ I continually see myself going down the rabbit hole discovering just how unaware of the rich biodiversity around me I really am.

The Green & Gold Coast

I was pleasantly surprised to learn that the Gold Coast region is the most biodiverse region in Queensland. On top of that, it is approximately 1% the land area of the Australian island state of Tasmania, yet contains more species of vascular plants then Tasmania.

Wet Schleophyl Forests

The Gold Coast is a treasure trove of biodiversity, and what is more surprising is the fact that this botanist has found that wet schlerophyl forests contain the greatest biodiversity.

Wet schlerophyl or hard leaved plants such as eucalypts are the predominant trees, and they contain an under storey of rainforest plants. This biodiversity is due to the cross over of both eucalypt and rainforest species.

Springbrook

David Jinks identified Springbrook as the epicentre for biodiversity In Queensland.

This mountainous area combines both rainforest and wet schlerophyl forests and are part of the ancient Gondwana forests. This area is part of the Gondwana Rainforests of Australia, which contains the most extensive area of subtropical rainforest in the world.

These rainforests are collectively a World Heritage Site with fifty separate reserves totalling 366,500 hectares from Newcastle to Brisbane.

Koalas in the Coalmine

Koalas, unlike plants, are a charismatic species. Most of us react with joy when we come across these furry cuddly creatures.

They spend a majority of their lives asleep high up in trees, digesting the cocktail of toxins found in their main food source, a select few species of eucalypts. Being nocturnal they often means that they aren’t often seen.

It is often when we find koalas in human environments, crossing roads or bailed up in a backyard by our pet dogs, do we see them. We may then if we are aware, make the connection that koalas are out searching for new habitat as their existing homes are threatened or cant sustain the current population.

Life In The Slow Lane

Plants unfortunately can’t move. They may reproduce and their offspring help to spread the species but this can be a slow process. Yet koalas, can be a sign that something is wrong. Koalas rely on plants for food and shelter, and as their habitat is destroyed it can bring awareness to the loss of our biodiversity.

Biodiversity Loss

Australia, just behind Indonesia has the notorious reputation for the country with the highest biodiversity loss. Our land clearing laws are a joke allowing prime habitats for many of our endangered species to be destroyed.

A few months ago, a large parcel of land containing prime koala habitat was totally cleared in Arundel. The Palmolive site was known to contain koalas, and as suitable habitat continues to be destroyed and fragmented we are in mortal danger of losing our national icons.

Relocating Koalas

As wildlife volunteers, rescuing koalas can bring about many moral and ethical decisions. One of these is to when relocate a koala. Studies have shown koala relocation have an approximate 50% rate of success. With such a large mortality rate, the decision to relocate a koala isn’t taken lightly.

This year the most prominent case for relocation was a male that was found on a busy suburban intersection. It was decided that to have the best chance of survival he would have to be relocated.

The decision to relocate this young male was made as he had no doubt been kicked out of his patch of forest by older males. However, he had got into a bit of strife as there was no longer anywhere else for him to go.

Koala Valley

It is incredible to think that to relocate a koala takes lots of paperwork yet to destroy their habitat is much easier to get official permission. As this male koala was going to be relocated further than 5km from his home range all the paperwork was sorted out.

We joined the carer and her family who had looked after this young koala to release him into his new habitat. An area was chosen, which was wet schlerophyl forest in a conservation reserve. We were all very worried about the survival of this healthy boy.

When we arrived at the forest, we climbed a hill that was in a little valley with a running stream and lush vegetation. Our fears disappeared as this habitat contained the prefect habitat of old growth trees and young lush eucalypts.

Wildlife Closed Doors

We have come to understand that koalas require very specific environments. Often the best land for housing is also the best land where koalas live. To offset the destruction of koala habitat, a developer may spare a portion of the land or offset it by planting trees on another parcel of land. The land that the developer may set aside may be hilly, scrubby and dry land that contains poor quality eucalypts that have little nutritional value for koalas.

These offset areas are set aside as ‘wildlife corridors’, yet often create barriers to the movement of wildlife as the quality of vegetation is sub standard.

The other way developers ‘offset’ their activities is by environmental offsets. This is where they plant trees often on a parcel of land some distance from the development site, sometimes it may be thousands of kilometres in a different state. This provides no benefits for the biodiversity within the development site or the koalas!

Indigenous and Endemic Species

The talk on the biodiversity of the Gold Coast highlighted to me the importance to distinguish between indigenous and endemic species. An indigenous or native plant species may found in a large region.

Queensland Bottle Tree

For instance, Brachychiton rupestris, commonly known as the narrow-leaved bottle tree or Queensland bottle tree, is found in a large region of Central Queensland. It is a common tree and described as of least concern.

I have a specimen that I am growing in a pot with beautiful finger like leaves. Mature species have a bulbous base, hence the name ‘Bottle tree’.

Ormeau Bottle Tree

David Jinks, mentioned in his talk Brachychiton sp. Ormeau or the Ormeau Bottle Tree. There are only 200 known individual trees in the wild and so the species is critically endangered.

The Australian Department of Energy & Environment describes the range of this species as such:

This iconic rainforest tree has a range of less than 1 square kilometre with only 161 individual trees. They grow to be over 120 years old and occur along creeks and rivers around the Gold Coast area.

The Ormeau Bottle Tree is an example of an endemic species. An endemic species is one that has a limited range. It is restricted to some natural areas of the northern Gold Coast, preferring undisturbed rainforest, more specifically along the Darlington Range in the Upper Pimpama and Albert River areas.

With such a limited distribution, and with very few individuals left in the wild, 140 individuals at one stage, there is a conservation plan in place to bring it away from the brink of extinction.

Bioawareness

So what can we do to be more bioaware? One place to start is our own backyard. If you have land for a garden why not consider creating an endemic garden as opposed to a native garden.

Endemic Garden

My property s a suburban block situated on a hill. I have a few large old eucalypts trees in my backyard. Very little would grow on the highest and furthest part of my backyard because of a combination of dry rocky shale and eucalypts that suck up all the moisture.

On top of that, I was given some ‘really good’ red soil by a contractor, a few years ago, who was building my driveway. It turned out that what he dumped on my front lawn was red clay filled with lots of Singapore Daisy seedlings. After many years of not being able to grow anything successfully, not even, hardy agaves, except for rampant Singapore Daisy weeds, I was about to give up.

Then after lots of money, time and hard work, we created terraces that we filled with quality garden soil and mulch many inches thick. We broke up the clay with gyprock and mixed it with the new soil. This provided a blank canvas to create our slice of paradise.

Native Garden

As mentioned before, bioawareness requires constant education. Instead of planting an endemic garden I had created a native or indigenous garden. But there is still room for me to add some endemics.

I was cognisant a couple of years ago to include species which were from the eastern seaboard of Australia, keeping away from West Australian species.

However, I didn’t know at the time where to get species that were specific or endemic to the Gold Coast. I have now found a few nurseries that sell endemic as well as native species.

A good place to start if you are interested in creating a an endemic garden is an app called GroNATIVE. You simply type in your postcode and it brings up a range of plants from large trees, to shrubs and ground covers found in your area together with local nurseries you can buy them from.

Growing endemic species in our suburban areas is a great way to help provide habitat and food for our native wildlife. They are much more suitable to local conditions as they have evolved to the local conditions over a very long time.

Botanical Garden

The Gecko (Gold Coast Environmental Council) talk by David Jinks on Gold Coast biodiversity inspired me to begin collecting rare and endangered endemic plant species.

I had previously researched the Ormeau Bottle Tree but wasn’t sure if it was being propagated commercially. I managed to track down a nursery in northern NSW that had a few specimens.

I made the trip down down and bought two small plants that were mere sticks with a few unhealthy looking leaves. The leaves looked very similar to my robust Queensland Bottle Tree that I have growing in a pot on our verandah. This tree has grown so quickly with all the rain and is almost as tall as me now. I’m hoping that my new acquisition will follow suit.

Mars & Madagascar

David Jinks mentioned in the talk that if we don’t maintain our biodiversity that we may one day end up looking like Mars. In other words, does biodiversity matter? Does it matter if we lose a few species here and there? Yes, it does. We are all interconnected in a web of life that we still know little about.

Losing a species like the Ormeau Bottle Tree, may not seem like much, as most of us haven’t even heard of this species. Yet, each loss moves us a step closer to this sad future.

It may sound like David was being overly dramatic with his Martian analogy yet it triggered in me memories of a visit to Madagascar 8 years ago.

We had been invited to visit the incredible effort that Eden Reforestation Projects was doing in Madagascar as we were and still are financial supporters of their work. We flew from the capital Antananarivo down to the west coast. As we flew in a Cessna over a desolate landscape of denuded red hills and bleeding rivers I was devastated thinking we were flying over Mars.

Losing Ground

Every square metre of land that we ‘develop’ without conscious and careful planning takes us one step closer to this apocalyptic vision of our natural world. While koalas may be the canaries in the coalmine, as they are highly visible when in our suburban humanscapes and being charismatic species, it is the plants that provide the habitat for animals that are often the silent victims of our greed and avarice.

Strong environmental laws together with programs such as the Gecko talks that increase our awareness of biodiversity will no doubt create a society where acts of environmental vandalism such as the destruction of koala habitat at Arundel will no longer be tolerated.

Seeing Connections

My fascination with our Australian bottle trees no doubt came about from biodiversity ignorance. Madagascar is famous for its Baobab trees. These trees superficially resemble bottle trees and I know that Australia has its own species of baobab.

In fact, I thought that bottle trees were a species of baobabs. It turns out that they are a totally different genus. They are found in arid regions not only in Madagascar, but also in Africa, Arabia, and as mentioned, Australia.

Baobab Forest

My love affair with baobabs and bottle trees no doubt came about from flying over the remote and stunningly beautiful Tsingy Forest in western Madagascar. These razor sharp limestone outcrops were once a coral reef that stretched for many square kilometres. Within this maze of limestone the majestic baobabs had taken root and I will never forget spending the night within the middle of this remote and strange world.

I felt like a modern day explorer discovering a world that possibly no other human had ever set foot on till our expedition party. The Tsingy Forest is almost impossible to traverse on foot, and with Google Maps the pilot was able to locate a clear landing spot, a depression within this forest of stone.

Connecting To Nature

Want to become more bioaware? Then I invite you to go down th rabbit hole in your local neighbourhood. To join, for instance, your local Landcare group that can help you learn about biodiversity while you help to rehabilitate local environments.

Maybe you may decide replace the monoculture of your water intensive green lawn with an endemic garden, whose plants have evolved to local conditions.

Seeing Green Not Being Green

As you go deeper down the rabbit hole, you will discover a greater connection to your local environment and the natural world. No longer will you suffer from ‘biodiversity blindness’ as David Jinks had so aptly described. It will fill you not only with an awareness but also a deep reverence, connection and appreciation for our local environment.

With greater awareness comes the power to affect change, to be part of the change you want to see in the world. Ignorance isn’t bliss. Bliss is to walk through a forest and to know and understand the individual plants and trees that make up the forest and their connections.

Intimate Connection

As I pen these final words I see thoughts intertwine and create connections. I think of where the word ‘endemic’ came from and how it originally meant ‘people belonging to a place’. I think of the Malagasy and how they live in a destroyed land vastly different to when they first arrived to the island of Madagascar thousands of years ago.

I think of the sense of discovery traveling through this incredible island, and how biodiversity has held on in pockets despite 90% of its original forests having been destroyed.

Looking at the image of the Malagasy women with their beauty mud packs on their faces I am reminded of Truganini, reputedly to be the last Tasmanian aboriginal.

Discovering Connections

I had an aha moment when I discovered her story in the Australian Museum in Sydney recently. It was the same feeling of excitement landing in the remote Tsingy Forest or reading about the critically endangered Ormeau Bottle Tree saved from the brink of extinction.

There was a description close by the portrait of Truganini, this noble woman. It read:

Our community today is very saddened, or get very upset with the global myth that Truganini was the last Tasmanian Aboriginal person, because generations have flowed from that time and will continue to flow. There will never, ever be no Tasmanian Aboriginal people. Never, ever.

Darlene Mansell

Tasmanian Aboriginal

First Australians, The Miegunyah Press, 2008

With these words I felt a sense of hope that just like cultural and human biodiversity, even in the darkest hours, life finds a way to survive and flourish.

Accessing Earth Through Heart

It also reminded me that like our Australian indigenous culture, we too must reconnect to the earth. We too must plant our feet to the ground and rediscover our connection to the natural world. Our indigenous culture has a vast storehouse of information and knowledge. They are intimately connected to the natural environment, and besides learning through reading and Western science, there is an area of knowledge that we may learn to access through spirit and heart.

It is through accessing this heart knowledge will we develop a deeper reverence and respect for the incredible biodiversity of our natural world and instinctively find our way back to earth.